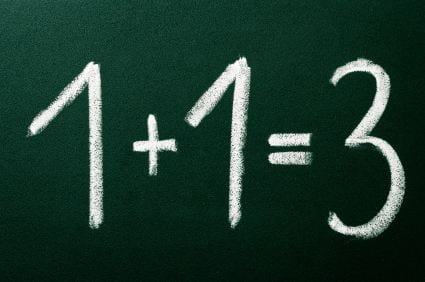

My school career, which has lasted for about a decade, has had both ups and downs in relation to my success, interest, and enjoyment. Like most students, however, one aspect throughout my years in school has remained: I am passionate and skilled in English and history but unable to comprehend the world of math and science.

For this reason, I would be described far differently by teachers and students depending on the class they see me learning in. For example, I am both knowledgeable of and intrigued by reading and writing. That is made clear by my internship with the Shaker Writing Center, in which I use this passion to mentor other writers. But on the other hand, I am the one being mentored by a tutor in math, which I have been doing since second grade. Many days in the cafeteria during the social lunch hour, you can find me at my filled table with a math packet and a confused look. When I ask my friends for assistance, I usually receive replies such as “we learned this like three years ago” or “how can you not figure that out?”

I also view most of what I learn in science as a foreign language; as an AP Spanish student, it is not one I can easily acquire. I struggle to put what I learn in this area into perspective. What does this combination of letters have to do with table salt or toothpaste? Is everything around me truly atoms and molecules? Why does everything have a charge, and what does this even mean? Unlike with science, in math, I can at least understand how I can use some of the concepts in the real world.

This math-inspired confusion I am prone to also causes awkward real-life experiences that leave me scorning the lack of balance between my understanding of numbers and words. The event I am referring to took place at work, where my typical task was to perfect meals at the request of the customers I spoke to. However, I occasionally managed the register, which I usually could do without stress. I say usually because customers usually would pay by card. But when customers came in paying with cash, I would often strangely ask for a co-worker to take over and pretend as if I had another task I had to attend to. While outside of school, I wanted no part of adding and subtracting decimals or converting metal coins to numbers in my mind.

As someone who finds humor in poking fun at myself, I went and told my friends this story after but used the explanation that I simply “don’t know how to count.” But my proclaimed inability to do any math whatsoever was contested by my success in the class, particularly this year. My math tutor explained to me recently that she believes I am skilled in the field. Having also worked with me in middle school, she expressed her belief that I developed struggling with math because I lacked the confidence that I could be successful with it. She further explained that I can do it so easily when working with her because I have gained pride in my abilities as a student. This proved true when I earned a high score on a math test soon after, which was congratulated by my teacher.

This inspired me to reflect on my experience at work. If I am finding success in math at school, am I truly so horrible in the subject that I cannot count change? I realized that I did not attempt to deal with the cash-paying customer and fail, but I abandoned the scene to avoid the possible difficulty. So perhaps my tutor was right, and I am not just unable to comprehend math but prone to feeling under-confident in my abilities in the subject.

So, what does this mean? Will I attempt to make my way into the most advanced math class at the high school? Will I strive to achieve a STEM degree? Will I work my way into NASA? Will I even claim to my friends that I am not as bad at math as they believe? The answer to all of these is no. My realization that I can be a successful math student does not that I should rise above others, but that I no longer need to swoop below them. I may have more skill in this area than I had previously believed, but I have no more interest than I ever did. Thus, I have no desire to proclaim to my friends any mathematical talent with my newfound mediocracy in contrast to the perceived atrocity I possessed before. Since I enjoy poking fun at myself more than I enjoy math, I intend to continue boasting my lack of ability. Despite only being skillful in certain areas such as English and history, these are also the subjects I am passionate about. Why waste my energy attempting to be good at what I hate?

After reading the story of my resentment for a topic and failure to perform well in it, followed by my realization that I can achieve success in it, and finalized with my pledge to retain my rejection of that topic nonetheless, one question remains: Why does any of this matter? Well, the moral of this story is that you will not find happiness by being good at everything. As I have explained, I am content with being average in math and science because I dislike them and am both talented and interested in English, Spanish, art, and history. But this applies to more than school. I am also a poor driver, but I accept this because I would always rather get a ride. I also I prefer running anyway, which I am good at.

So, embrace your flaws. Exaggerate what you lack skills in. Have fun making fun of yourself. But remember not to let this undermine your confidence because you are likely not as bad as you claim.

Evan,

This is really insightful. I love this sentence: “I also view most of what I learn in science as a foreign language; as an AP Spanish student, it is not one I can easily acquire.” It made me think, then chuckle. I admire your self-reflection and self-acceptance.

Dude I needed this one! Self-acceptance 🙂

The second I saw the title, I knew this was going to be about disliking math and I knew I could relate to everything you said. Math is overrated anyway 🙂