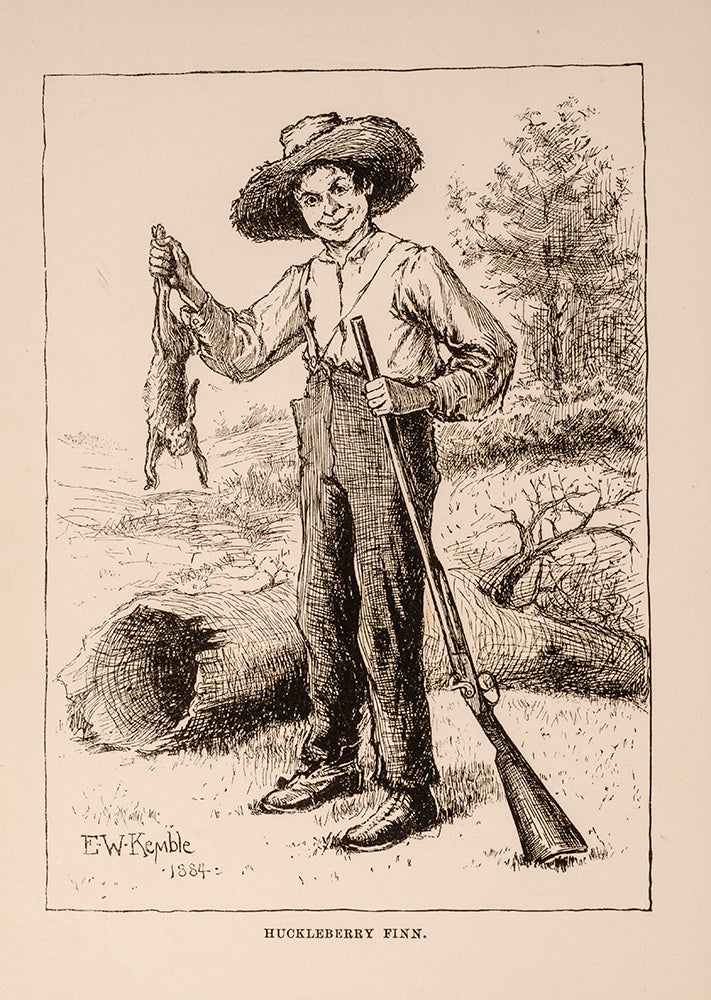

When reading fiction, a special bond forms between the reader and the narrator. We engage with the constructed world as though we are a character in the story. It fosters emotional connection and drives the plot forward. We’re all familiar with first person narration. Most works of fiction utilize the style, from classics such as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to contemporary novels such as The Hunger Games.

When reading fiction, a special bond forms between the reader and the narrator. We engage with the constructed world as though we are a character in the story. It fosters emotional connection and drives the plot forward. We’re all familiar with first person narration. Most works of fiction utilize the style, from classics such as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to contemporary novels such as The Hunger Games.

It’s a simple narrative technique and doesn’t seem to contain any particular flair or pomp beyond the events of the story. Writing in first person is a natural extension of human discussion. At its most basic, it is a recounting of events, like an old friend telling you about their weekend.

As a result of its reliability, writers use first person constantly. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it just makes it harder for one particular work to stand out from the pack.

Good writers use narration to deliver their stories. Great writers use narration to enhance their stories. There are 3 novels I shall discuss that particularly demonstrate the impact that narrators have on the writing they deliver.

(Spoilers follow. Tread carefully)

Earlier I mentioned the casual nature of first person. Mark Twain highlights this feature in the aforementioned Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Huckleberry Finn’s command of language is weak. His grammatical conventions are inconsistent and his syntax is juvenile. However, these imperfections serve a distinct purpose. Not only do we see Huck’s adventures through his eyes, but we hear it through his voice. He’s naive, young, poor and simplistic. And it shows. He reminisces about past schemes, and crudely comments on his experiences. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn surrounds the reader with Huck’s thoughts.

It’s textbook first person. Huckleberry Finn is the story-teller through and through. Twain sought to illuminate the experience of a boy coasting down the Mississippi River. Morally, he is torn between helping Jim, or returning him to Miss Watson. Having access to Huck’s inner thoughts illuminates this dilemma. The reader’s literary experience lurches with the current of Huck’s conscious. We are effectively pulled down the Mississippi on the same raft as Huckleberry Finn and Jim, subject to all its twists and turns, as frightening and exciting as they may be.

My personal favorite novel, The Great Gatsby, goes in a slightly different direction. Nick Carraway generally lacks passion and personality. He routinely plays second fiddle to the larger-than-life Jay Gatsby and lacks Tom Buchanan’s arrogant and bombastic nature. Nick really isn’t the central character of his own universe. Frankly, he doesn’t have to be. His relative indifference illuminates Gatsby as a grandiose and mystical figure.

The other components of Fitzgerald’s novel make up for Nick’s comparative dullness. He’s perceptive enough to let others shine, and other characters often trust him enough to share some of the saucier elements of their personal lives. By making Nick the narrator, Fitzgerald treats the reader to a personal story without compromising Gatsby’s mystery. Nick isn’t the one that’s Great, but part of Gatsby’s greatness comes from his indulgent facade.

All we learn about Gatsby comes directly from Nick’s observations and experiences. This style distances the reader from the book’s wealthy and sultry namesake. Even as Gatsby’s closest confidant, Nick doesn’t entirely understand what makes him tick. At times the reader gets the impression Gatsby isn’t in control of himself. When he meets up with Daisy in Nick’s home, Gatsby is disorganized and nervous. He fiddles incessantly and contemplates abandoning the whole ordeal. Throughout the novel, the reader isn’t quite sure why Gatsby does the things he does. He constantly says “old sport” and accepts blame for Daisy’s vehicular incident. The reader and Nick can infer Gatsby’s intentions and motives, but there is a clear wall between the story being presented and the mind of the cryptic metropolitan.

I do not like George Orwell’s 1984. I think it’s profoundly dull, sounding less like a story and more like a manifesto-in-denial. But even I must admit Orwell employs a deeply engaging narrative style. 1984 is deeply personal, depicting Winston Smith’s thoughts and struggles in a repressive society. Throughout the book, we are constantly informed of what Winston knows to be true.

At least, what he thinks he knows to be true.

While the two books I mentioned prior featured first person narrator-reader interactions, 1984 includes no such thing. The story is narrated in third person limited, so Winston never directly communicates with the audience like Huck or Nick. But instead of sounding cold and detached, the novel brings us directly into Winston’s mind in a strange, roundabout way.

The narrator’s diction is absolute. They don’t simply relay Winston’s thoughts to the reader, they relay his conviction. When Winston is particularly sure of some Party plot, the narrator mirrors his certainty. Phrases like “Winston confidently thought X” are replaced by “He was sure of X. It was so obvious, anyone paying attention would know within an instant.” Such language slowly molds the reader’s worldview to fit Winston’s. The narrator undermines the unfortunate truth facing Winston, instead bolstering his (often incorrect) judgments about the nature of his life. By the book’s conclusion, it is painfully obvious that Winston has been actively and persistently deceived. As Winston’s taste of freedom is ripped from his hands, the reader learns he was never as safe as he thought. Orwell presents a narrator who is deeply attached to the protagonist. This narrator is untrustworthy not because they are dishonest, but because they cling to a character who is wrong.

Narration profoundly impacts every work of fiction. Deliberate and conscious decisions ensure a novel’s narrator will actively contribute to the story’s literary value. In the case of theses 3 books, the authors turn a seemingly simple decision into a profound tool to subtly enhance their writings. So the next time any of you indulge in writing fiction, take a moment and think; Who should tell my story?

what tha HECK 19844 is tha BEST book iv evar read