I have this memory of when I was a kid. I don’t know how old I was, but it was a Sunday in July, and I’d just left Church. I’d ran away from my Ma, down the alley, across the street, past Sokolowski’s, over the fence, and down to the waterfront. The weather that day was extreme—it must have been something like a hundred degrees, and there wasn’t even a suggestion of wind. Now, I’ve spent a ton of days by the river, but that day always stuck around in my head, because when the first breeze in forever came rolling in, it carried this smell that made me tear up, it stunk so bad. I used to love staring out past the stacks, past the old iron bridges, past the abandoned trains, and just take in that heavenly skyline. But that time, the heat must have stirred up something deep beneath the water, because that smell was enough to ruin the whole city right then. It was like the smell of stuff no one was supposed to know about. I’m lost as to what it was, but that was the closest thing to what I was smelling now.

I dragged my watering eyes away from the action and focused on the ring itself. It seemed to stretch all around the room; fifty feet at least. Fifty feet of interlocked wood and steel. Looking closer, I spotted a chunk of scaffolding from some old construction project. It had this mark spray-painted onto it, though it took some time to notice it; the surface was so worn and dirty that the paint was nearly invisible. On both sides were numerous boards, each one held to the next by nails or wire—though, in some places, the nails had been rusted into no more than stains on the wood, and the wires wound so tight they cut into it. Further along, there was this stretch of chain link fence, from an old schoolyard. It was shackled to a mass, made from planks nailed side by side in these oddly neat rows. The white paint looked half recent, though it had begun to chip—a front porch. Whether the house had been foreclosed, demolished, or someone just jacked the porch when no one was looking, it was here, and it wasn’t being stood on. Neighbors weren’t chatting on it. Parents weren’t watching their kids on it. No carpenter built it thinking it would end up being used to make dogs fight. It had been repurposed.

As my eyes came back around, they stopped at another piece, this one being used to prop up a slab of plywood. This structure, two posts attached at the middle in an X shape, was tilted on its side. A face glared out, twisted with pain. Its eyes looked afraid and hopeless. The nose was pinched in disgust. Its gaze was not towards the center of the ring, but upward, as if straining to look for another face in particular. As I looked at the carved body, spread on the posts, I saw the stains of blood. Taking a closer look, I realized that some of the bloodstains were from the rusted wire, and others were old paint meant to look the part.

The floor of the ring was soft dirt, that had been poured onto the concrete. Black and brown were the only two colors on the floor. Aside from the places where paws had dug into the ground for leverage, the entire arena was raked smooth and even. All appeared as it should.

One of the dogs was a lean mutt. He had struck the first blow, and now he was fixing to strike the last. His opponent was a big black beast, whose fur was spotted white. This one had this huge brow that hung real low over his eyes, like a bulldog. It sunk especially lower on the left, so he looked like he was giving everyone the stink-eye. He was a real bruiser—you could just see it in the way he stood; as if the ground was all he had left. The other one, the younger I figured, he was constantly on the attack, snarling and foaming and gnashing and nipping, never easing up.

From the outside, you could almost laugh, watching the dogs rip into each other for no reason. It was only funny if you weren’t paying attention. I was. I could see that for both of them the fight was real, and totally legit. To the mutt, the bruiser was what stood between him and life. And the bruiser was in the same place. To either, the other was just some stranger coming onto their turf talking big, claiming they deserve this and that. Who’s to say that if there wasn’t a ring, this fight wouldn’t still go down?

“That one’s Champ, right?” I asked the man beside me, regarding the big black hound. His name was Mikey.

Mikey puffed one last time on his cigarette, took it out and nodded at me. “Yeah, that’s Champ,” he answered as he changed his mind, put the cigarette back in his mouth and had another puff, leaving it there. “As of now, he’s eleven-and-oh. He’s where you want to place your bets, man. The little guy doesn’t stand a chance.”

“Eleven-and-oh,” I breathed to myself, focusing on Champ, who had fought eleven times before. Looking closer, I realized that the white spots were actually places where the fur had been ripped out, or the skin had scarred. And where his brow sagged low over his left eye, I realized that the eye was gone, torn out in one of eleven previous encounters. I put my hand to the pendant hanging on my neck, as sort of a knee-jerk reaction.

The action had slowed down for the moment. Both were beat up and bleeding; they were well matched, and both had an equal right to their life. Jeers from the crowd rang, taunting them to keep on fighting. However, the younger dog had focused his attention on something that had appeared as the dust settled. Sniffing it, he nervously backed up and began to whine. I peered down to see a canine jawbone, half buried in the earth.

Champ didn’t react. This dog wanted to finish the fight, so he could go back to his cage, and be left to starve again until the next fight. He knew it would be this way until the day he lost. And when that day came, there would be new dogs to fight, to dream of winning as he did—like his opponent does. They will have that dream crushed all the same. There have been fights going on long before him, and they would continue long after. Such is the way of things, and even a dog can come to understand that, after eleven fruitless battles.

The young dog recovered, and began again to froth and jump at Champ, who still stood unflinchingly. They fought. When the younger dog bit Champ, he bit back, and on and on it went, until the younger dog flipped Champ on his back and tore out his throat. The crowd I stood amongst went wild, half with fervent cheer, the other with disappointment. Champ lay unmoving on his back, dark blood running out of his torn neck into the dirt. The younger dog picked anxiously at Champ’s carcass. Money was trading hands all around me. I just stood there and watched.

Champ looked a mess. His feet were splayed out, and his fur was glazed red. The blood that came pouring out of him could have turned the arena into a pool—I finally understood the reason for the dirt. It did a great job of holding liquid. Like a sponge. His guts had loosened upon death, and waste was oozing out along with the blood. Apparently, that happens when animals die. Watching Champ die, I figured out what the smell was.

Mikey was shaking his head in good-natured disappointment. He was $10,000 in the hole, but he could make it back twofold in the next match if he placed his bets right. “Well, good for the little guy, I guess,” he laughed.

The little guy’s owner had come forward and chained him up again, and was in the process of giving him a cheap steak as he ushered him back into his cage. He was a happy dog for a day. He had beaten his enemy. His cause was virtuous. He felt like a winner for once, and he loved his master for it. I pitied the poor ignorant creature—his owner had been one of the people to lose money in the round.

I approached a group of men sitting around laughing. They all were smoking—not cigarettes, but big smelly Cuban cigars—illegal. Someone must have broken out a box in celebration. These were the bosses, who made money off all bets made. There were five of them, all gathered around a table, and made plans for the next series of fights, now that a reigning champion had been defeated. They were the ones who owned this and a number of other sites, employed men to work here, and reached out to handlers, inviting them to bring in their dogs. Regardless of who lost, these five men always won.

They were all roughly the same size, all of them well dressed. Some had hair, others none, some had earrings, others necklaces, some were fatter, others thinner, but all of them had handfuls of rings and dark Italian suits. Without the bling though, they all looked average. Without this operation, they were nothing. My attention was momentarily diverted to the back wall. There were dozens on dozens of cages, each covered in a black towel. I knew that there was a dog in every cage, sitting quietly in darkness. They didn’t know what they were in for. I found myself filled with a terrible rage. I wanted to see these men fill pools with their own blood. I wanted to see every one of those cages opened and see the dogs tear through the den, removing this stain from humanity.

I returned to myself and came to the table. At first, they didn’t stop laughing and talking to acknowledge me.

“Excuse me,” I interrupted—ineffectively. They were even noisier than before. “Excuse me,” I said, matching their volume.

One of them looked up at me and smiled, and the others grew quiet. “Alright, buddy. You have our attention. What’s the deal?”

I froze. I wanted to say so much to them, to ask them how, or why. At this point they were all looking at me, waiting in silence for me to declare my business. Then the one closest to me broke it.

“You wanna know why we get to do this?” he asked, in a way that made it unclear whether he expected a response. He had a necklace peering over his shirt, where it was unbuttoned. A little silver crucifix hung. Christ’s face looked up in agony. I knew exactly who he was looking at this time. I didn’t answer, so he continued. “We’re on the right side of the ring.” And they all broke out into a laughter.

I laughed too. “I guess that’s true. Sorry, I’m a little out of it today. My name’s Simon. I talked to your man Mikey, and he said you were interested in the pits I have.”

The man in the middle leaned forward, “Hey-ey, you’re Simon!” He put down his cigar and stood to shake my hand. We shook hands. His were clean and smooth. “Yeah, yeah, I remember. Mikey told me you have some badass dogs on your hands. Pits, you said?”

“Yeah, they’re out in my van. You want I should get them now?”

The man approved.

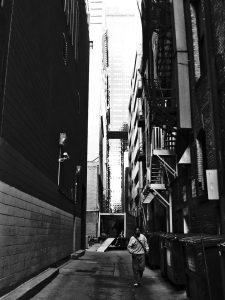

On my way to my car, I went past the ring. The dirt was fresh and raked smooth, as if there had never been a fight earlier. It was totally clean. All the crowd had mostly left, except for a few of the handlers, and some of compatriots of the middleman. Coming to the exit, I stepped aside for someone walking out at the same time. He was this huge, balding man, with coarse hair covering his arms, hands, and neck, and likely everywhere but his head. He was wearing a rust-stained apron and had with him a garbage bag, filled and tied. I followed him out into the alley, where we diverged. There was a dumpster to the right, which he opened with one arm, and with the other slung the bag. I had a good guess about what was inside.

“Is that Champ?” I asked him, regarding the bag.

“Oh, no,” he chuckled. “Plain old garbage. We don’t throw away the dogs. Waste not, know what I mean?”

I knew exactly what he meant. That would explain the apron. I couldn’t open my mouth, so I said nothing and turned.

He called, “If you’re coming back, you want me to hold the door?”

I didn’t respond, but he held it anyway.

I opened the back of my van, where the two cages were. I didn’t dare lift the towels as I carried them back inside with me. I didn’t want them to see anything—not each other, not where they were going, not me. They were quiet. Sleeping.

~Epilogue~

I drove off in my van twenty grand richer. When I made it to the house, it was still dark. Jan was asleep in bed. I stashed the cash under the mattress and fell over onto it. After a second, I jumped up and ran to the bathroom, my stomach heaving. I clutched my cramping guts, and opened my mouth, ready to vomit. But the wretching was dry, and nothing would come up. The back of my throat burned, as if some demon stood behind my tongue, jabbing me with his acidic fork. I suffered there for close to an hour, just wretching endlessly. The whole time I still had the stench of the dogfights on my nose.

After I had picked up the courage to stand again, I did. I leaned over the bathroom sink, rinsing out my mouth directly from the old faucet. I looked at myself in the warped reflection the faucet showed me. My face was blurred, dull, stretched, and round, but I could still recognize myself. In that imperfect mirror, I looked as gray and old as I felt. The man in the faucet looked at me with a look of shock and denial. Hanging down by the drain was my cross. The Lord was looking up at the faucet, with that same look of agony and fear. And disdain.

I ran, putting on my jacket hastily, rushing out onto our front stoop, past the old metal post that had once kept our dogs leashed. Down the lawn I walked, out the metal gate, slamming it quickly. I halted before my van, and turned back, through the gate, up the lawn, and to the door. I’d almost forgotten to lock up. Checking the handle once, then twice, then a third time, I got back to my van, and sat for a while with the key in the ignition. I didn’t know where I could go. I looked in my rear view mirror, staring at the empty space behind me. Then I had an idea. I drove to the alley behind the church. But I stopped again. I couldn’t go to the church. That was where the good go, and therefore I could not. I got out of my car and started towards the waterfront, where I went as a kid. Even out on the waterfront, I felt nothing and smelled the same smell. I looked out onto the water. I started to wade out into the scum, imagining I would just go out there and sink. But I could not, for my legs refused to take me any further. I stood up to my knees in filthy water and sobbed. I had no power even to grant myself the mercy of death. And still, the stink of dogfights clung to everything. Ultimately broken, I turned back and looked out.

I was in the guts of the city, but the skyline still appeared far off and lofty. The tallest towers stood in the distance, cloaked in darkness; an infinite number of glowing windows shone, though the towers themselves matched the shade of the four o’clock sky. They loomed. To all of us, they were symbols of the city—great monuments to the American dream. Anywhere in the city, they were sure to be seen hulking over—the watchers of every happening within. When I looked at them now, however, they laughed at me, and at the dogs I sold, and at the smell that plagued the entire city, as it plagued my nose. It was the scent of every dead dog in the city, as well as that what killed them. We were living in it. And up there, in the dark heavens, they kept on laughing.